PODCAST

Water Works: An Aquatic History of Milwaukee

Episode 8: The River Keepers

Host: Jonathan Stuever

Blog: Marisa Camacho

The Milwaukee River is home to an iconic corridor run by the Milwaukee County Parks. There are 28 miles of hiking, biking, and water trails totaling 178 acres of trails and green space. The Milwaukee River brings together a community that loves fishing and recreation for everyone to enjoy. However, it has not always been this way. The Milwaukee River has come a long way and yet still has a long way to go from the damage done.

Today, Milwaukee is known to be an AOC—or an area of concern listed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. These clean-up efforts overall are relatively new and more important than ever. It was not too long ago that Milwaukee’s waters were used as a trash can. Out of this emerged some serious efforts focused on cleaning up Milwaukee’s blue spaces. In 1994 The River Revitalization Foundation was founded by two larger service clubs in Wisconsin: Kiwanis Club of Milwaukee and the Rotary Club of Milwaukee. From there they became Wisconsin’s only urban rivers land trust. They protect land and water resources for the public benefit. River Revitalization helps preserve green space along Milwaukee’s rivers by purchasing land, acquiring easements, seeking land donations and managing public lands.

In addition to their efforts, The Milwaukee Riverkeepers work effortlessly alongside amazing volunteers to protect, improve and advocate for water quality, riparian wildlife habitat, and sound land management in the Milwaukee, Menomonee, and Kinnickinnic River Watersheds.

In this episode we look at the essential progress made to the Milwaukee River from industrial ruin and earth moving operations, among other things, to pollution removal and revitalization.

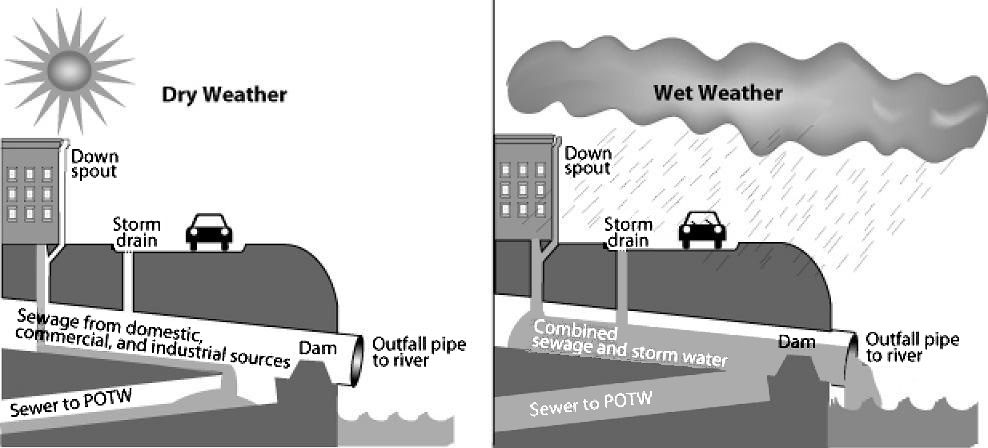

This infographic shows the processes of dry weather and wet weather sewer flow. We can see the overwhelming effects of rain on our sewage system. Check out more information on this and what The Milwaukee Riverkeepers are doing to monitor pollution at their website.

Episode 7: Cleaning Up Our Act

Host: Tony Viccari

Blog: Christopher D. Cantwell

The city of Milwaukee’s water supply was in something of a crisis in the latter half of the twentieth century. Unregulated and unchecked use—and misuse—of Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee River had turned them into some of the most polluted bodies of water in the country. This was beyond the management of wastewater we’ve discussed in earlier episodes. This is the result of a century of industrial pollution and use. The city was in dire need of a movement to restore its most vital resource before it became irrevocably damaged.

But in a fascinating turn of events, Wisconsin’s efforts to clean up its waterways would help launch today’s modern environmental movement.

Central to this story is the life and career of Gaylord Nelson. A native of Clear Lake, Wisconsin, Nelson served as both a state senator and governor before eventually being elected to the United States Senate in 1962. As a senator, Nelson made conversation his signature issue, pushing both Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson to make the preservation of lakes and rivers for public use a priority. As part of this effort, Nelson drew a page from the student movements of the 1960s and helped organize the first “Earth Day” in 1970, which was comprised of a number of “teach-ins” and demonstrations across the country.

One of the sources used to tell this story comes from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s TMJ4 archive. UWM holds tens of thousands of hours of old TMJ4 footage, including several speeches and appearances by Nelson. To see one of the addresses Sen. Nelson gave on Wisconsin’s pollution problem, check out this entry in the archive.

Episode 6: The Battle for Blue Space

Host: Marisa Camacho

Blog: Marisa Camacho

Throughout this podcast series we have seen how water impacts so many distinct aspects of daily life. Where there are people and where there is a question of access there is policy. In this episode we look at the ways in which water is political and the socialist roots Milwaukee carries. Milwaukee is unique to the public access of green and blue spaces and has historically been very protective of these areas.

The public trust doctrine has been under fire previously in Milwaukee. Milwaukee’s famous Harbor House restaurant war arguably developed on a filled lakebed illegally in the 1960s. It was originally called the Pieces of Eight, owned by Specialty Restaurants Corp. out of Los Angeles. By the 2000’s philanthropist and retired business executive Michael Cudahy bought out the lease for $1 million. Cudahy partnered with restaurateur Joe Bartolotta to propose a new restaurant, which city officials approved in 2009.

It is not clear why, but the DNR failed to challenge the development and therefore, the Common Council approved the lease. The restaurant was granted a 21-year lease with three 10-year renewal options — the last renewal expired on Jan. 31, 2018. The Public Trust Doctrine applies to all navigable waters, which are defined as any waterway on which it is possible to float a canoe or small watercraft at some time during the year. According to the public trust doctrine, filled lakebed, the area east of N. Lincoln Memorial Drive is supposed to be available specifically for public use. This includes parks, museums, and the Summerfest grounds.

In the new lease agreement, they confront the murky violation of the Wisconsin Constitution and must continue to take steps to accommodate the public.

- $15 daily lunch special,

- patio tables set aside for the brown bag lunch crowd

- public use of Harbor House’s restrooms.

- pays 2% of its annual sales

- five free parking spots continue to be set aside for public use

To learn more about the public trust doctrine: https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/Waterways/about_us/whyRegulate.html

Episode 5: Under the Surface

Host: Krisenda Henderson

Blog Post: Marisa Camacho

Do you know where your water comes from? Do you know where your water goes when it flows down the drain? You may have a vague sense that it in some way involves Lake Michigan, but do you really know? Well, if you can’t answer these questions, this episode is for you.

In this episode we look at the history of water through the lens of infrastructure. We take you along the journey as water flows from Lake Michigan through the pipes under our feet and back out again. In particular the episode talks about, well, how do I put this…poop. Not literal poop, mind you, but the city’s need to manage its sewage and wastewater. And that effort has had diametrically opposed impacts in Milwaukee’s history. In the early 1900s, at the height of Milwaukee’s Socialist days, the city turned its sewage and the bacteria it fed into a revenue-generating form of fertilizer called Milorga nite. But in the 1990s, when one of the city’s filtration systems failed, those bacterial sources led to the infamous Cryptosporidium outbreak.

nite. But in the 1990s, when one of the city’s filtration systems failed, those bacterial sources led to the infamous Cryptosporidium outbreak.

This duality speaks to just how essential water is to our social life, and how managing it is central to the quality of that life. This episode touches on this and so many other aspects of Milwaukee’s history.

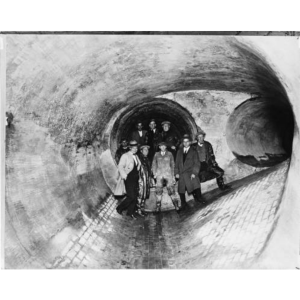

Right: City workers inspect a new sewer line, sometime in the mid-1900s. From the UWM Archives.

Episode 4: Shipwrecks

Host: Mike Reno

Blog post: Mike Reno

The loss of the Lady Elgin in 1860 is an event that has gotten an outsized and at times overembellished presence in Milwaukee’s collective memory. The Lady Elgin was a passenger steamship on Lake Michigan back in the run up to the Civil War. This episode presents material on the leadup to the disaster sitting it in the context of the time, where various racial, ethnic, and political issues were dividing the country in half.

There are two specific items at the Milwaukee County Historical Society that regarding shipping and the Lady Elgin that I would like to draw your attention to. First, is the Lady Elgin Collection. The collection consists of a timetable, song sheet, newspaper clippings/articles and other miscellaneous material. Especially, if the song sheet was a song that the passengers were singing in, “the party like atmosphere” that prevailed onboard the ship as it headed out into the foreboding waters.

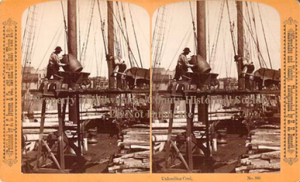

Second, is this photo from the Historical Society’s collection of workers offloading coal from a ship. The lady Elgin dealt with many aspects of Milwaukee’s past, from social, political, to technological issues all inherent in that disaster. However, the one aspect that the Lady Elgin did not address at least directly, was economic issues. This is a photo of workers unloading coal from a ship docked at Milwaukee’s harbor.

Episode 3: Bridge War

Host: Oscar Harding

Blog post: Oscar Harding

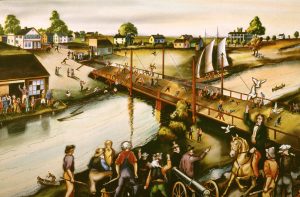

The Bridge War is a curio that many Milwaukeeans may be vaguely aware of – an amusing sidenote in the city’s history, as locals engaged a series of petty squabbles surrounding a number of bridges that were built, demolished then rebuilt. But this would be a disservice to the magnitude of the “war” – it was the conflict that ultimately led to Milwaukee becoming a city.

Violence doesn’t just erupt unless there are already significant tensions in play, and the then-village of Milwaukee was a tense place. Consisting of three settlements, separated by the Milwaukee and Menominee rivers and named after their founders – Solomon Juneau, Byron Kilbourn and George Walker – Milwaukee was a place desperately in need of bridges.

After denying Milwaukee’s eastern and southern wards – Juneautown and Walker’s Point – a bridge for years, Byron Kilbourn was the first founder to build a ramshackle bridge to his western ward, Kilbourntown, in 1840. Pretty soon after, Juneau constructed the Chestnut Street bridge – now known as the Juneau Avenue Bridge. Over the next few years, three more bridges appeared. It was Juneau’s ward that paid the most for all this construction, but Kilbourn’s ward saw it as a threat to their monopoly on business.

Pretty soon after a schooner crashed in Kilbourn’s Spring Street Bridge – now known as the Wisconsin Avenue Bridge- rumors began to circulate that its captain had been paid to do so by the east ward, who were fed up of paying for Kilbourn’s bridges. Eventually the west ward decreed that the half of Chestnut Street bridge in their territory should be torn down, a nonsensical decision that resulted in the entire bridge collapsing into the river.

Despite the founders’ best efforts to ease tensions, the east and west wards continued tearing down bridges. Reconstruction was supervised by armed guards. The conflict made Milwaukee a statewide laughing stock. Juneau, Kilbourn and Walker realised something needed to be done – the settlements needs to unite.

Kilbourn and Walker realised something needed to be done – the settlements needs to unite.

Following rapid approval by referendum, a city charter was adopted by the three wards and the city of Milwaukee was born, with Juneau elected as its first mayor.

Episode 2: Millennial Thinking

Host: Elizabeth Loomer

Blog post: Chris Cantwell

The “One Dish One Spoon” law discussed in the episode, which is sometimes also called the “Dish With One Spoon,” is believed to have guided indigenous understandings of resource use since at least 1142 CE. The phrase evokes an image of multiple people or communities eating out of one dish with one spoon, which sets the expectation that one party will be sure to leave enough food for the other party. This, then, applied to the ways in which communities drew upon the waters and the land.

The ”One Dish One Spoon” philosophy describes both the indigenous practice of resource use, and names specific treaties that tribes signed with each other. In 1701, for example, representatives of several Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee nations met in Montreal to sign a peace treaty that created shared hunting grounds. Indigenous oral traditions relate that a wampum, or bead, belt depicting a single kettle or dish was created to commemorate the treaty. Both the belt and the principles it embodies remain central to native communities today, as we discuss in the episode. The image below, for example, is of a t-shirt one can purchase from the Seneca-Iroquois National Museum in Salamanca, New York.

Episode 1: “Water Spirits”

Host: David Zeh

Blog post: Marisa Camacho and Chris Cantwell

Indigenous tribes built mounds honoring animals and spirits that served as ceremonial, spiritual and practical purposes, marking territories and gathering places. Though few remain today, the mounds remain important both to the native tribes who built them, and to the state’s history as a whole. In fact, Wisconsin is home to more effigy mounds than any other state in the United States.

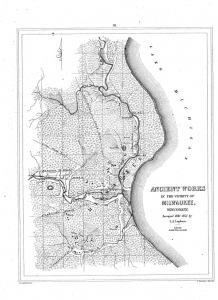

Below is a scan of one of the earliest maps of the Milwaukee area’s mounds. Drawn by Increase Lapham, who host David Zeh discusses in his episode, the map shows just how prominent these earthen works were in the area. Lapham’s labeling of these features as “ancient,” meanwhile, reveals the effort by white settlers to drive native peoples from the land by claiming they had no claim to the present. You can read more about Lapham’s work here.

Season 2: Water Works Preview

Milwaukee is a city built in, on, by, and around water. And so it’s worth considering how our understanding of the city changes when we look at its longstanding relationships with the rivers, lakes, and streams that surround it. How does it influence our lives? And how does it shape our heritage?

This podcast seeks to answer these and other questions. Last year our show took a deep dive into how the 1918 spanish flu outbreak could help us understand the COVID-19 pandemic today. This year–with the Milwaukee area witnessing a persistent drought, and Lake Michigan seeing both record high and low levels–we ask how an understanding of Milwaukee’s historic relationship with water might shape how we confront future challenges.

2021 Series: The Healthiest City

Episode 1

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 4

Episode 5

Episode 6

Episode 7

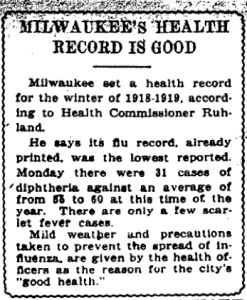

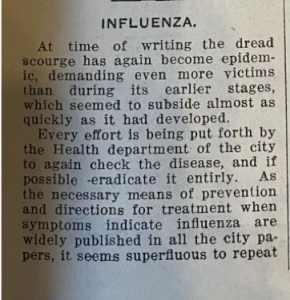

In the winter of 1918, the city of Milwaukee found itself in the midst of a crisis almost exactly like our own. A highly contagious and deadly disease that had spanned its globe found its way into the city, causing alarm. This disease was the great influenza outbreak, or “Spanish Flu,” of 1918 and 1919. And like the coronavirus pandemic today, it upended life in our city. Schools shut down. Businesses shuttered. Hospitals filled up. And people died.

In the winter of 1918, the city of Milwaukee found itself in the midst of a crisis almost exactly like our own. A highly contagious and deadly disease that had spanned its globe found its way into the city, causing alarm. This disease was the great influenza outbreak, or “Spanish Flu,” of 1918 and 1919. And like the coronavirus pandemic today, it upended life in our city. Schools shut down. Businesses shuttered. Hospitals filled up. And people died.

What can we learn about our own moment by looking to the past? What can Milwaukee’s other pandemic teach us about navigating our own crisis?

The Healthiest City is a podcast that seeks to answer these and other questions. Hosted by Professor Chris Cantwell of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and produced by students in his “History and New Media” course, the show is made in partnership with the Milwaukee County Historical Society. Over the course of seven episodes, it explores how Milwaukee’s teachers, bars, physicians, nurses, public health professionals, and everyday citizens dealt with the influenza, and compares their experience to our own.

The Healthiest City is a co-production of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Department of History and the Milwaukee County Historical Society. It can be found wherever you get your podcasts. New episodes post every Monday.

Episode 7

Host: Madelyn Lampark

Blog Post by Madelyn Lampark

It will be obvious to those of us who have lived through the COVID-19 pandemic that the consequences of the Spanish Flu epidemic were not limited to its health and mortality implications. The flu disproportionately affected young men and women of working age; quite unlike the typical distribution for influenza deaths, which primarily affect the elderly. The loss of a not insignificant portion of the world’s labor force was bound to manifest in economic and social consequences.

The First World War is often identified for its role in hastening the spread of the flu, yet non-participation alone did not prevent the spread. Both Sweden and Norway remained neutral during the war and still experienced the same level of mortality as the United States and Europe. In Norway, the effects of the Spanish flu hindered the development of community-based economic cooperatives for 25 years. In Sweden, the effects of the flu resulted in a decrease of capital returns and an increase in the population living in poorhouses. Despite the decrease in the labor force, researchers found no corresponding rise in earnings.

Flowers from Hugo Klemmer’s memorial service at his home in 1918. Photograph generously shared by Jane Gapinski.

Some researchers have argued that the epidemic contributed to the onset of the brief, post-WWI recession. In the US, those states with the highest levels of mortality also had elevated rates of business closures between 1919 and 1921. Much of the subsequent economic growth of the 1920s appears to be merely a return to the pre-epidemic trend.

Episode 6

Host: Frank Kalisik

Blog Post by Brianna Quade

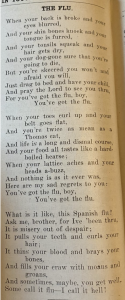

Poem printed in Keeping in Touch Magazine, printed by Gimbels Department Store, Milwaukee County Historical Society Collections

On October 11, 1918, Commissioner George Ruhland issued his public health order closing city establishments in response to the outbreak of the Spanish Flu. Within a few months of this order, by Janurary 1919, Milwaukee’s businesses were back to normal. But within those three months, department stores and theatre’s were upended, whereas bars and saloons were able to stay open.

“All places and establishments of every nature within the city of Milwaukee carried on by any person or persons, or corporations detrimental to the public health and likely to spread such contagious disease, be closed during the period of the present emergency. All saloons shall be closed excepting such saloons which do not allow a gathering of people on the premises excepting for the purpose of taking meals.”

Puddler’s Hall, the second oldest tavern has some experience with pandemics. Opened in 1873, Puddler’s first operated as a union hall for local iron workers. It was bought in 1909 by the Pabst Family and ran as a “tied” house, meaning it exclusively sold Pabst products. Saloons, shopping and theater/live entertainment were central to Milwaukee’s social culture. However, in October 1918, these businesses were upended as the looming threat of the Spanish Flu entered the city.

Specifically for theaters like the Empress, there was an estimated $100,000 loss in ticket sales a day during the mandatory shut downs. This left many traveling burlesque troupes, stranded. At this time, burlesque was a major source of entertainment in Milwaukee’s. Unlike how burlesque is thought of today, in 1918, these performances were very similar to vaudeville. Milwaukee’s boasting theater scene had around 70 movie houses in addition to “legitimate theaters” that put on stage performances.

With bars and saloons able to stay open, theaters and department stores were closed entirely. Theaters, like The Empress Theater, one of the most prominent theaters in the city, were unable to pay their workers, which left five traveling burlesque troupes stranded in the city. Bearing the brunt of the shut down order, unemployment in theaters led those out-of-work actors to department stores like Gimbels, who was in need of additional workers to handle the holiday rush.

“Because of the prevalence of influenza our regular force was considerably reduced in many departments necessitating employing an unusual number of ‘extras’ for the holiday season. This doubtless affected the good service we were able to render to our patrons in previous years. However, since all large stores were working with the same handicap, the public generally appreciates the difficulties under which the store were working. The Schuster stores engaged several hundred extras, perhaps double the number employed in past holiday seasons.”

Because of the rapid response to the pandemic, stores were not as effected as other businesses. Still, department stores took public health seriously. They changed store hours, limited crowds, and enforced Commisioner Ruhland’s orders. With their compliance, they helped limit the spread of influenza. If they had not done so, the situation may have ended quite differently.

Printed in Keeping in Touch Magazine, printed by Gimbels Department Store, Milwaukee County Historical Society Collections

As the pandemic came to a close in Milwaukee, businesses slowly went back to normal. However, bars and saloons faced another threat: prohibition. On January 16, 1919, the 18th Amendment was ratified, prohibiting the sale and transport of liquor. Many bars like Puddler’s got creative and turned their spaces into speakeasies in basements to continue the flow of that necessary ale. While saloon business was upended, department stores were poised to take over the market. After two months of social distancing to slow the spread of the flu, and over a year of sacrificing for the war effort, Milwaukee consumers crowded the stores in celebration.

Episode 5

Host: Christina Grev

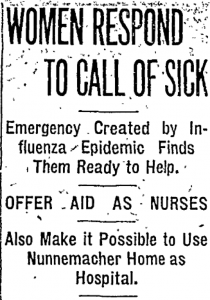

Blog Post by Ken Bartelt When the Spanish Flu reached Milwaukee in the fall of 1918, the entire city mobilized to combat the spread of the disease and care for those afflicted with the illness. While all Milwaukeeans played a part in the city’s effective pandemic response, women played a particularly important role. Whether their contributions took the form of the out-of-work teacher volunteering to nurse at the temporary hospital established in the Nunnemacher house, the traveling nurse going door-to-door to care for children whose parents were sick with the flu, or as an emergency ambulance driver, women played an unmistakable role in making Milwaukee the “Healthiest City” during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

When the Spanish Flu reached Milwaukee in the fall of 1918, the entire city mobilized to combat the spread of the disease and care for those afflicted with the illness. While all Milwaukeeans played a part in the city’s effective pandemic response, women played a particularly important role. Whether their contributions took the form of the out-of-work teacher volunteering to nurse at the temporary hospital established in the Nunnemacher house, the traveling nurse going door-to-door to care for children whose parents were sick with the flu, or as an emergency ambulance driver, women played an unmistakable role in making Milwaukee the “Healthiest City” during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

When Health Commissioner George Ruhland ordered the closure of Milwaukee’s schools, many teachers, the vast majority of them women, found themselves without work. Since Milwaukee’s public school teachers were considered government employees, the city’s health department devised a creative way to use these idle teachers in the fight against the flu. In order to collect data on the spread of the flu in the city, the health department employed teachers to canvass the neighborhoods in the vicinity of their schools, making visits to each house and recording all cases of the flu that they found for the health department. Without the work of these teachers, the health department’s understanding of the flu’s spread in the community would have been greatly diminished.

Some women worked as traveling nurses, visiting Milwaukee homes to care for flu patients and their children. One of these nurses, identified as “Miss Kruse,” reported the following:

“In a few places I found the entire family, consisting of six or seven, all in bed with the ‘Flu.’ The majority of those cases ran high temperatures, which necessitated considerable nursing care. In some cases where the mother was in bed several small children were running around in night clothes and bare feet. These had to be washed, dressed and fed. No neighbors would offer to help because they are afraid of getting the ‘terrible disease.’”

Miss Kruse’s report demonstrates the risk that these nurses took in caring for flu patients. While neighbors avoided the sick so as not to become ill themselves, Milwaukee’s nurses could not socially distance themselves, and as the Milwaukee County Historical Society’s Kevin Abing explains in episode 5 of The Healthiest City, many nurses became infected with the flu themselves. Undoubtedly, the bravery of these nurses saved many Milwaukee families from the Spanish Flu’s most devastating outcomes.

Episode 4

Host: Dan Koehler

Blog Post by Dan Koehler

On Thursday, September 12, 1918, sharp-eyed Milwaukee Sentinel readers might have noticed an obscure article buried near the bottom of page 10. It appeared just above a cartoon strip called “Somewhere in Milwaukee”, making fun of citizen complaints concerning government-ordered World War I conservation mandates. The comic, by someone named “Long”, probably got a lot more attention for its mocking of whining Milwaukee residents complaining about what they were doing without during the war than the article entitled “Malady Reaches America, Returning Transports Bring Spanish Influenza to U.S., Officials Believe.” It was the first warning Milwaukeeans got that the Spanish Flu had landed on the eastern shores of America. In part the article informed readers that:

“There is little means of combatting the disease except a definite quarantine and that obviously is impossible at this time because it would require interruption of intercourse between communities as drastic as was resorted to in the dreaded days of yellow fever in the south. Precautionary measures are considered the best weapons to combat the malady and as the disease is a new one to American physicians, the government possibly may take the menace in hand by issuing country wide warnings and general instructions of how to avoid the infection if possible and how best to meet it if it be contracted. Spanish influenza, although short lived and of practically no permanent serious results, is a most distressing ailment which prostrates the sufferer for a few days which he suffers the acme of discomfort.”

Two days later, the Sentinel published remarks by then-US Surgeon General Dr. Rupert Blue to the Associated Press indicating that children in schools might be at high risk of infection:

“There is no such thing as an effective quarantine in the case of pandemic influenza, but precautionary measures may be taken and should be taken. Thus far we have little information as to susceptibility of children, but it is fair to assume that this type of influenza might spread through a school as easily and rapidly as measles for example.”

In the absence of agencies like today’s Center for Disease Control or a cadre of government epidemiologists, Dr. Blue’s occasionally published general observations and benign suggestions were about all the help that state and local health officials could count on. For local health professionals everywhere in the US in 1918, the Spanish Flu epidemic became a true test of their public relations and persuasion skills, along with their medical training, in an era of limited information about how pandemics worked.

Episode 4 of our podcast The Healthiest City focuses on Milwaukee Health Commissioner Dr. George C. Ruhland – an early local version of today’s Dr. Anthony Fauci – and his efforts to inform residents of the dangers of the Spanish Flu epidemic while monitoring and containing its rapid spread throughout the city in the fall and winter of 1918. We take a deeper dive into how the disease affected Milwaukee public and parochial school children and their teachers, and how both became soldiers in Ruhland’s “army” to combat the flu after he issued the first or a series of closure orders in October.

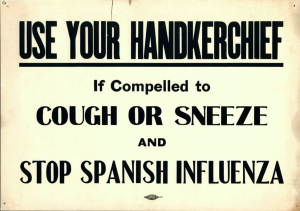

Ruhland worked side-by-side for months with doctors, nurses, city officials, teachers, business leaders and newspaper reporters to keep Milwaukee residents apprised of progress in the fight against the dreaded disease with only limited state resources and virtually no help from Washington DC. In scenes that are remarkably reminiscent of 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic, Ruhland pleaded with city residents to cover their mouths and noses with handkerchiefs when sneezing or coughing, limit exposure to others in elevators and office buildings, avoid riding streetcars and crowds or having any contact with people showing signs of the disease. With the flu spreading at an alarming rate and afflicting residents in numbers far beyond what Ruhland originally thought possible, and with no end in sight by mid-October, he ordered Milwaukee movie theaters, places of amusement, taverns, restaurants, and schools either closed completely or severely limited in operation.

And just when Ruhland gained the upper hand with the epidemic in Milwaukee and eased off the closures, the Great War came to a sudden end. Milwaukeeans took to the streets to celebrate, causing what can only be described as super spreader event that ignited a second wave of the disease – and another round of business and school closures.

If this sounds familiar, then we think listeners of Episode 4 will be reminded once again that history really can, and does, repeat itself.

Episode 3

Hosts: Christina Grev and Katie Bischof

Blog Post by Ben Schultz

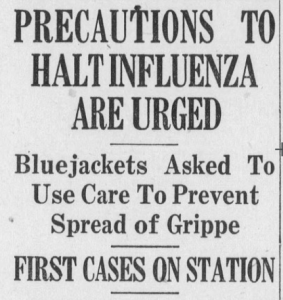

The Great Lakes Bulletin announces the first cases of the flu at their base. (Source: Illinois Digital Newspaper Collections)

We highlighted the USS Leviathan in this episode, but we felt that the story deserved a little more elaboration. The Leviathan was originally built as a German luxury liner known as the Vaterland. The US Navy captured the ship in 1917 and converted into the country’s largest troop transport, capable of ferrying thousands of servicemen across the Atlantic. But when the flu pandemic struck Europe the following year, the Leviathan’s enormous capacity, packed with people in ways her designers had never imagined, preventative measures against the spread were impossible and the results were nightmarish.

The Leviathan left New York Harbor for her ninth troop transport to France on September 29, 1918. The ship quickly filled with over 12,000 passengers and crew headed to the front, some of whom struggled to even make it on board in time for departure because they were already severely ill with the flu. While some of the sick were left behind in New York, the disease still spread uncontrollably and infected thousands during the ten-day voyage.

The USS Leviathan in full camouflage (Source: Naval History and Heritage Command)

By all accounts, conditions on the Leviathan were horrifying. Most of the ship had to be converted into a makeshift hospital. A report later published by the Navy stated that “pools of blood from severe nasal hemorrhages were scattered throughout the compartments.” Eighty passengers were buried at sea during the trip, and dozens more died shortly after arrival. Over a thousand more troops were so sick that they had to be carried to base camp. All this came just weeks before the war would end.

A homecoming event for soldiers returning to Milwaukee, January 1919.

(Source: Milwaukee County Historical Society)

Meanwhile, the Great Lakes Naval Station in Illinois, situated along the Lake Michigan shoreline about halfway between Milwaukee and Chicago, was serving as the largest naval training facility in the world. 45,000 men were stationed there in the fall of 1918, when the base became the first location in the Midwest to report a case of the flu. Within a week, 2,600 of them had fallen ill, many times more than the station’s medical facilities could handle. Troops leaving the base to visit family or to go on furlough introduced the virus to much of Illinois and Wisconsin for the first time.

At the urging of Milwaukee health commissioner George Ruhland, the Navy agreed to stop allowing troops to go on leave. This move certainly helped to slow the spread of the pandemic into Milwaukee, but it came too late to halt the virus. The first person in Milwaukee to die of the flu was K.C. Adams, a private in the Marine Corps from Memphis, who had been in the city on leave.

On the same day that Adams died, September 24th, the Great Lakes Station announced that it would still be holding its weekly review of troops the following day. Two weeks after the first cases in the camp, and with thousands of men sick, the station was still inviting visitors to see and meet with their troops. At the last minute, however, the review was canceled as the epidemic worsened. Ruhland successfully urged the Navy to place the Great Lakes Station under strict quarantine.

Episode 2

Hosts: Bailey Green and Roman Lulloff

Blog post by Ben Schultz

Between the catastrophic smallpox outbreak of 1894 and the influenza pandemic of 1918, Milwaukee continued to face challenges in the field of public health that we were only able to cover briefly in this episode. Two of the most prominent health issues in Milwaukee during this period were milk contamination and tuberculosis, both of which the Socialists worked to combat when they gained power.

In 1912, W.H. Meyers wrote that “no article of the household ranks in importance with milk—upon no other single article in the family dietary so greatly depends the health and well-being of all its members, both old and young.” But, Meyers warned, the most important part of a family’s diet was also the most susceptible to dangerous chemical changes, which could make it unfit for human consumption. When it was improperly produced or distributed, milk could easily spread diseases like ptomaine poisoning and typhoid fever.

When Emil Seidel was elected Milwaukee’s first socialist mayor and the Socialist Party took control of the Common Council in 1910, they took these risks seriously. They passed an ordinance in 1911 requiring the Health Department to inspect food and milk. Milk, among other things, needed to be tested for bovine tuberculosis, as it could easily spread to humans. In his memoirs, Seidel described the ordinance as one of a handful of highlights of his administration, alongside the building of public drinking fountains and the first municipal electric power plant.

The reforms passed by the Socialists when it came to dairy safety are reflected in “The Laws and Ordinances Relating to Milk,” a 29-page booklet published by the Milwaukee Health Department in 1914. “It shall be the duty of the bacteriologist” and their deputies, the booklet stipulates, to visit and inspect “any store or building, platforms, establishments or places of any kind containing milk or cream, and ascertain or examine the condition thereof with reference to cleanliness and sanitation, and they are authorized, directed and empowered to cause the removal and abatement of any unfit, unclean or injurious condition.”

The cover page of “The Laws and Ordinances Relating to Milk,” a 29-page booklet published by the Milwaukee Health Department in 1914. (Source: Google Books)

But milk wasn’t the only area of life where 1910s Milwaukeeans needed to worry about contracting tuberculosis. Health department bulletins of the time warned people that dust could spread the disease, and offered ‘dos and don’ts’ to those quarantined with it in the form of an article titled “Quarantine Sense and Nonsense.” For example, tuberculosis patients were asked not to “write unnecessary letters,” and encouraged those who received

One bulletin in 1913 reported that “recently a case was called to the attention of the Division of Tuberculosis of a man who was said to live in a ‘rat hole.’” His dark and musty apartment was mostly below ground, and had become “inexpressibly filthy.” The bulletin continued: “a nurse was sent to make a call and learn the conditions. She reported that in all her experience she has never supposed that human beings could exist in such a place as she found.” Accordingly, even after the man was taken to the hospital and his apartment was fully fumigated, the health department declared it unfit for human habitation.

For Socialists like Emil Seidel, tuberculosis wasn’t just a sickness, it was a symptom of the squalid conditions laborers were forced into. And the Health Department endorsed this view, concluding in the case of the man in the ‘rat hole’ that “basement dwellings, as long as they are cheap, will be used for human habitation in Milwaukee, unless they are prohibited by law, and tuberculosis will certainly develop where there is no light, no air and people are underpaid, under-nourished and overworked.”

The Muirdale Sanatorium in Wauwatosa was established by Milwaukee County in 1914, and treated tuberculosis patients until 1970. (Source: MCHS)

The decades-long fight against tuberculosis gave Milwaukee crucial experience with isolating and quarantining the sick, experience that was bolstered by the Socialists’ efforts to eradicate the disease and the social factors that bred it. This experience paid off in 1918, as we’ll see in future episodes.

Episode 1

Hosts: Olivia Hoff and Maddy Tabor

Blog post by Ben Schultz

In the late nineteenth century, the city of Milwaukee was on the rise. The city’s industries drew many people seeking jobs and opportunity. The prosperous city also boasted one of the most prominent public health plans in the United States, capped off in 1877 with the construction of the Milwaukee City Hospital. But less than twenty years later, Milwaukee would be caught in the throes of the worst epidemic the young city had ever seen.

Judy Leavitt, author and historian of medicine, describes the smallpox outbreak of 1894 as an anomaly. By the time it hit, Milwaukee had well-established public health programs to administered smallpox vaccines, but these vaccines were not regularly monitored. The public could pick up “vaccine points” at any drug store, small pieces of ivory with sharp tips covered in the smallpox vaccine, which could be introduced into the bloodstream when the ivory was scratched against the skin. However, because of the inconsistency of regulation and administration of the vaccines, many people became wary of them. An anti-vaccination group started in Milwaukee in 1891, just three years before the city faced the worst smallpox outbreak in its history.

When the outbreak hit, many locals placed the blame on the German and Polish immigrants of the city’s South Side neighborhood. These immigrant groups lived in crowded tenements that were poorly maintained by landlords and city officials, and to make matters worse, the city’s official public health recommendations were only written in English, a language many immigrants could not speak, let alone read.

Walter Kempster, then the city’s public health commissioner, refused to understand the cultural barriers between the German and Polish people. He did not rally community organizations such as the Red Cross or local churches to distribute and interpret public health recommendations. Instead, Kempster’s primary response to outbreaks in these neighborhoods was to send city officials to affected homes to take children away to isolation hospitals, sometimes by force.

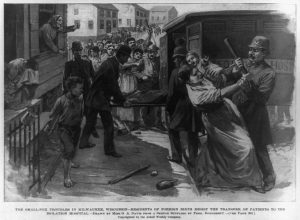

Many of the city’s immigrants, by contrast, believed that families should take care of their sick in their own homes. They did not trust the government to return their loved ones after being in isolation, and Kempster’s forcefulness often reminded them of the repression they had fled in Europe. As a result, families and their neighbors rioted against public health officials who tried to take children to the hospital, fighting them with “domestic weapons” such as salt and pepper, rolling pins, and anything they might have at home. Meanwhile, the smallpox outbreak only grew worse.

A news illustration drawn by Georgina Davis shows “residents of foreign birth” rioting against health officials taking a child infected with smallpox to the isolation hospital. (Source: Library of Congress)

Walter Kempster’s recommendations were based on robust scientific research, but he failed to communicate them effectively to the public, and they became counterproductive. As the riots died down, the Milwaukee city government realized that major changes needed to be made to their public health department. Health recommendations were published in German and Polish for the first time. Kempster was removed from office by the end of the year, although he would later hold the position again in 1898.

The smallpox outbreak of 1894 made Milwaukee’s government realize the need for its community to know and understand the policies that directly affect them. 24 years later, what the city’s public health department had learned from the experience would be put to the test as an influenza pandemic emerged.